Introduction

One of my first posts was an initial Framework for Analysis. The premise was the universally accepted fact that there was an event on September 11, 2001. I developed a neutral framework that allowed anyone to present a body of evidence that included pre-facto, facto, and post-facto information to support their definition of the event. No one has set forth a credible thesis that the event was anything other than a terrorist attack because there is no body of evidence to support a different conclusion.

The body of evidence assessed by both the Congressional Joint Inquiry and the 9-11 Commission is convergent and conclusive that the event of 9-11 was a terrorist attack. Therefore, I used the framework for analysis to outline the basics of the event as a terrorist attack in my first article.

In this article, I will describe the attack in more detail and will also examine the Nation’s response. I will again identify the battle commanders and will establish the battlefield. Then we will discuss the attack and the government’s counterattack. Finally, I will set the stage for the Nation’s transition to Operation Noble Eagle. The history of that operation is being written by United States Air Force historians.

The Battlefield and the Battle Commanders

On 9-11, nineteen terrorists commandeered four aircraft to mount a multi-prong attack against the National Airspace System (NAS), the battlefield. The NAS is a component of the larger National Transportation System. The attack also impacted at least three other national systems; defense, preparedness (emergency response), and policy (continuity of government). In this article I will focus on the NAS and one defense component, the U. S. air defense system.

The NAS is operated by the Federal Aviation Agency’s (FAA) Air Traffic Control System Command Center (Herndon Center), commanded by a National Operations Manager (NOM). Benedict (Ben) Sliney was the NOM on 9-11.

The NAS is defended by the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), which is divided into regions, one of which was the Continental U. S. Region (CONR). The east coast of the U. S. was the responsibility of one of CONR’s sectors, the Northeast Air Defense Sector (NEADS). Air Force Colonel Robert Marr commanded NEADS on 9-11.

Sliney and Marr were the nation’s battle commanders that day. Given that the attack on 9-11 was a battle in a larger war against terror, Sliney and Marr were the highest level personnel who could take any timely action that morning. As we have discussed elsewhere in a series of articles on Chaos Theory, information did not flow concurrently to Sliney and Marr, or between them. They never talked to each other during the battle.

The Flow of Information

The battle commanders did not talk to each other for two primary reasons. First, as we have discussed elsewhere, Boston Center (ZBW) preempted the hijack protocol and, in the terminology of Chaos Theory, established ZBW and NEADS as “strange attractors,” the focal points for the exchange of relevant information.

Second, no one at a higher level, in particular the battle managers, Maj. Gen. Larry Arnold, USAF, at CONR, and Jeff Griffith at FAA Headquarters, had the situational awareness to force the flow of information to be between NEADS and Herndon Center. A chart I prepared while on the Commission Staff illustrates the flow of information to and from NEADS, during the period 9:21 to 10:22. Note that the flow of information during the time that AA 77 and UA 93 were an issue was between NEADS, primarily the identification technicians, and the regional air traffic control centers.

The Attacker’s Tactical Advantage

At the strategic level, the hijacker planners achieved a basic principle of war, surprise. The surprise was so complete that the attack proceeded as planned until the passengers and crew aboard UA 93 learned what was happening. At the tactical level, the hijackers got within the government’s decision cycle and stayed there for most of the battle. In the vernacular, the government was always playing ‘catch up ball.’

The counter attack gained its only tactical advantage when the Langley fighters established a combat air patrol (CAP) over the Nation’s capital. According to the 9-11 Commission Report: “At 9:46 the Command Center updated FAA headquarters that United 93 was now ‘twenty-nine’ minutes out of Washington D.C.” The CAP began at 10:00; the projected UA 93 arrival was 10:15.

The Attack

The attack lasted for four hours and 18 minutes, beginning at 5:45 a.m. when Mohammed Atta and one accomplice entered the NAS at Portland, Maine and ending at 10:03 a.m. when UA 93 plummeted to earth near Shanksville, Pennsylvania.

Dulles, Boston, and Newark airports were the primary line of departure, and all four targeted planes were scheduled to take off in a short time span centered on the eight o’clock hour. I have speculated elsewhere that Atta’s entry into the NAS at Portland was a preliminary line of departure, simply a “Plan B,” a contingency to ensure that if all else failed, he and one accomplice could complete one prong of a planned four-prong attack.

The attack had a northern and a southern component, each two-pronged. In the language of Chaos Theory, that unfolded as a nonlinear double bifurcation which overwhelmed a nation determined to follow existing linear response systems.

The Tactics

The attack was a simple plan: commandeer four aircraft through violent, expedient means and fly them into buildings. The tactics were equally simple. A Commission Staff Report of August, 2004 summarizes events concerning the takeover and control of each hijacked plane. First, overwhelm the crew, kill the pilots, and then fly the planes to their targets. Second, manipulate the transponders to cause problems for air traffic control. A previous post, “Transponders and Ghosts,” is my assessment of that tactic.

The hijackers had sufficient knowledge from their cross-country orientation flights as passengers to know the variances between scheduled and actual takeoff times. They tended to fly United for their orientation flights, so they also knew that it was possible for United passengers to listen to flight deck air traffic control communications on cabin channel 9. They also gained a sense of the habits and tendencies of cabin crews and knew they would be preoccupied once the seat belt light was turned off. Further, they purchased their tickets close enough to September 11 to have some degree of confidence from long-range weather forecasts that it would be a clear day on the East Coast. Their overall planning was meticulous, detailed, and, ultimately, successful.

The final line of departure and point of most likely failure was security screening. We can estimate that the line crossing began around 7:00. There is no video record of when the hijackers passed through security at either Logan or Newark. The hijackers entering the NAS at Dulles passed through security screening beginning at 7:18 and began boarding about 30 minutes later.

That allows us to speculate that the pass through security screening began about 30 minutes prior to boarding at the other two points of departure. That extrapolation means that al Shehhi and his crew passed through security prior to Atta and his crew; the UA 175 crew began boarding at 7:23, the AA 11 crew at 7:31. This analysis is supported by a three-minute 6:52 call to Atta from, most likely, al Shehhi. That was the “go” signal for al Shehhi to enter and Atta to re-enter the NAS.

(Note: bolding above added on Feb 7, 2010. Atta had to pass through security a second time at Logan.)

The sequence of entering the NAS at Dulles provides a glimpse into the detail that went into the plan. At Dulles, two hijackers preceded the designated pilot through the checkpoint, followed by the pilot and then the last two hijackers.

That pattern was replicated with minor variation during the boarding process. In each case, two hijackers preceded the designated pilot on board, followed in three cases by the pilot, either alone (AA 77) or with a colleague (AA 11 and UA 175), and then followed by the rest of each crew. The one exception was UA 93. Jarrah was the last to board.

The first hijacker boarded at 7:23, UA 175, and the last boarded at 7:55, AA 77. The boarding window of exposure across all four flights was just over 30 minutes. I estimate that the window of exposure to enter the NAS, to pass through security, was about the same.

We can extrapolate that the pattern of passing through security at Logan and Newark was identical to Dulles: accomplices first, followed by the pilot and rest of the crew, in some order. Why might this be so? A simple answer is that the pattern did not expose the pilot immediately, allowing him the opportunity in every case to abort if his accomplices encountered difficulty.

Once the hijackers were through security and on board the aircraft, three additional distinct, measurable events defined the attacker’s entry into the NAS; cabin door closed, push back, and liftoff. A detailed discussion of those events is beyond the scope of this paper. Suffice it to say that each event took the passengers and hijackers further away from local and airport security and to a point where the only security was provided by the air crew. None of the four hijacked aircraft had an air marshal on board.

For our purposes in this paper, the time between push back and liftoff is defined as the delay time. According to the August 2004 Commission Staff Report the average delay time for AA 11, UA 175, and AA 77 was approximately fifteen minutes. By contrast the delay time for UA 93 was nearly three times as long, 42 minutes. That establishes a “delta,” a delay approximating 30 minutes, the difference between expectation and reality. The UA 93 prong of the southern attack lagged well behind plan, giving the government’s counter attack a chance, as we shall later see.

AA 11 pushed back at 7:40 and lifted off at 7:59. UA 175 pushed back at 7:58 and lifted off at 8:14. AA 77 pushed back at 8:09 and lifted off at 8:20. UA 93 pushed back at 8:00 and lifted off at 8:42.

Situation Summary

At this point we need to pause for a moment and take stock of the situation. By 8:20, three hijacked aircraft were airborne; and the fourth, UA 93, would have been if we consider the “delta” of 30 minutes. At Herndon, Ben Sliney, in his first day as the NOM, was in a routine morning meeting. At NEADS, Col. Bob Mar was in the battle cab, an unusual situation predicated on scheduled exercise activity for the day. The battle cab was fully staffed, and he had a designated exercise mission crew commander, Major Dawne Deskins, USAF, to assist.

No one at any level anywhere in the government, the airlines, or on board the four targeted aircraft was aware that the attack had been underway for well over two hours and that a well-timed assault was imminent.

The Assault

AA 11. Atta struck first, quickly, a short 15 minutes or so after liftoff. Within no more than three or four minutes, his crew secured the cockpit and Atta was in command of and flying a domestic commercial airliner. A few moments later, he announced his success to the NAS, “we have some planes.”

Some hold that announcement to be evidence of Atta’s poor skills and ineptitude. I find that position ethnocentrically deceptive and a gross underestimation of the terrorist threat on that day and in general. I hold, based on Atta’s demonstrated ability to plan in detail, that his broadcast was intentional, for two reasons.

First, it was possible that al Shehhi could hear him on cabin channel 9 aboard UA 175. There is no evidence that he did, but we do know that Atta’s transmissions “on frequency” were heard by the UA 175 crew; AA 11 and UA 175 were on the same frequency during the time span of Atta’s transmissions. The UA 175 pilot/co-pilot reported the fact to New York Center as soon as the plane was handed off by Boston Center. Second, I credit Atta with wanting the NAS to know there “were some planes,” to introduce uncertainty into the system, chaos if you will.

UA 175. UA 175 lifted off at about the time the assault began on AA 11. Al Shehhi waited until the plane was in New York Center airspace before he struck. He would have known that fact by listening to cabin channel 9. Further, my assessment is that the plan was to hijack each plane in the airspace of a different NAS air control center.

Al Shehhi’s crew assaulted the cockpit immediately after the crew had made its report to New York Center, 28 minutes after liftoff. As was the case with AA 11, al Shehhi was in command of UA 175 within minutes, certainly by 8:46 when the transponder code changed concurrent with the impact of AA 11 into the World Trade Center north tower. The code changed again within a minute.

I asked the UA senior pilot to demonstrate changing the transponder code on a similar aircraft, made available for us to explore, guided by the senior pilot. The transponder knobs were arranged as two stacks of two each. The senior pilot demonstrated a two-step process. The first step changed the first and third digits; the second and fourth digits then defaulted to zero. The second step changed the second and fourth digits. The new codes for UA 175 were 3020 and 3321, respectively. UA 175 morphed in the air traffic control system to be a transponding intruder.

AA 77. Hanjour’s crew assaulted the cockpit a little over 30 minutes after liftoff. There is no known correlation to the takeovers of AA 11 and UA 175, but AA 77 was hijacked soon after the takeover of UA 175 and at about the time that New York Center knew it had a problem with UA 175. As with the other flights, the takeover was swift and sure. Hanjour was in command by at least 8:56, when the transponder was turned off.

There is no evidence that the hijackers knew that a transponder turned off during a turn would cause the problems it did for Indianapolis Center. The tactic was likely simply one in a series of distinct transponder manipulations designed to present a different problem set for each of four air traffic control centers. In this case, the plane was assumed lost and reported as such to the Air Force Rescue Coordination Center.

UA 93. Jarrah was the most disadvantaged of all the hijacker pilots. He had only three accomplices, his plane was over 40 minutes late in departing, and he and his crew waited an additional 46 minutes to assault the cockpit.

The assault occurred around 9:28 and, as in the other three cases, was swift and sure. Within a few minutes, Jarrah was in command. He turned off the transponder well after the turn back east, which presented little problem to Cleveland Center in maintaining spatial continuity on the aircraft. Cleveland Center successfully used the same tactic which Boston Center tried, without success, planes in the air to sight and report UA 93’s position.

We can extrapolate that had UA 93 departed on time his takeover would have been virtually time-concurrent with the takeover of AA 77.

Assault Summary

In every case, the cockpit was secured by the hijackers within a few minutes, at most five and, more likely, two to three. In each case, the transponder was manipulated differently, each manipulation presenting a different situation to the NAS. With the flights commanded by terrorist pilots, it was left to their accomplices to control the cabin. Three crews did so successfully; the fourth did not.

We do not know what the hijackers expected by way of a counterattack or if they expected one at all. We do know the details of the counterattack and we turn to Chaos Theory for our discussion.

Chaos Theory and the Counterattack

Chaos is deterministic. It is not random and can be bounded. One key to managing chaos, therefore, is to reduce the bounds and concurrently to limit uncertainty. Chaos is also self organizing and information flow in a chaotic situation follows the path of least resistance. Another key to managing chaos is to direct the flow of information to those who can take coordinated action, in this case Herndon Center and NEADS.

Herndon Center was established to manage chaos on a daily basis. One of its main concerns is weather, and it is no accident that one of the key positions on the Center floor is Severe Weather. Intuitively Herndon Center knew that the flap of a butterfly’s wings somewhere would bring instability to the NAS. Herndon Center had procedures in place to manage chaos.

NEADS was also established to manage chaos; it never knew what any given day’s activity would bring. As with Herndon Center, NEADS had procedures in place to manage chaos.

I know of no evidence that anyone in the government or in the military had ever introduced NEADS and Herndon Center to each other prior to 9-11. NORAD exercise scenarios speak to the testing of command and control procedures with “FAA,” but nothing apparently happened to cause the NOM and NEADS commander to pick up the phone and talk to each other. They certainly did not do so on the morning of 9-11.

Procedures

Ben Sliney and his NAS managers had at least three procedures available to them to manage chaos: ground stops, airborne inventories, and ACARS messages to cockpits. Herndon Center deferred to the airlines in the latter case.

Colonel Marr had specific activity centers whose sole reason for existence was to reduce uncertainty. Foremost were the identification technicians, dedicated enlisted women and men who were under the clock to identify unknowns by reaching out to whoever had actionable information. He also had surveillance technicians, equally dedicated enlisted men and women who were also under time constraints to track unknowns, given actionable information. Finally, he had weapons controllers and a senior director, experienced officers, whose job was to scramble, vector, and control air defense aircraft to targets provided to them.

The Counterattack

The counterattack began at 8:25 when Boston Center declared AA 11 to be hijacked. It ended 95 minutes later, at 10:00, when the Langley fighters established a combat air patrol over the nation’s capital. Shortly thereafter, there was nothing more to counter–the attack had ended.

Early indicators were picked up by both Boston Center and American Airlines; both followed existing linear processes, assuming that this was a singular event that would follow historic procedures. All that changed when Atta came on the air.

Boston Center managers soon comprehended that their report of a hijack was not going to initiate hijack procedures to the military and they took matters into their own hands. Within 13 minutes, they had figured out how to reach NEADS, both through Otis TRACON and direct to NEADS. The air defense response began at 8:40, and planes were in the air 13 minutes later.

The knowledge that there was a second plane came at 8:53 when New York Center realized it had a problem with UA 175. The plunge of UA 175 into the World Trade Center south tower caused the air traffic control system, working in concert with the Herndon Center, to immediately put in place a series of ground stops: Boston at 9:04, all traffic through/to New York at 9:06, with both Centers at “ATC Zero” by 9:19.

At that same time, United Airlines began sending specific warnings about cockpit intrusions to its airborne pilots. United 93 received such a message at 9:23, according to the dispatcher. Herndon Center considered such contact to be an airline prerogative and deferred to them. United Airlines dispatchers had begun contacting pilots as early as 9:03, but not initially with specific warnings. The first contact was to inform the pilots that aircraft had crashed into the World Trade Center.

With the knowledge that Atta said “we have some planes,” and with the emerging information that AA 77 had been lost by Indianapolis Center, Herndon Center initiated a nationwide ground stop at 9:25. An order for an airborne inventory swiftly followed.

The airborne inventory confirmed that AA 77 was lost and soon surfaced that fact that UA 93 “had a bomb on board.” The counterattack was gaining momentum but was still outside the decision cycle of the attackers.

With the further knowledge that a fast-moving unknown, in reality AA 77, was approaching the nation’s capital, Herndon Center, by 9:45, ordered all planes to land nationwide. That mission was accomplished by 12:16, according to the Administrator’s briefing book.

Herndon Center and the Air Traffic Control System used the tools at their disposal to try and bound the problem. They were outside the attackers’ decision cycle in every instance. They used one of the two keys we mentioned to manage chaos. They did not use the other: Herndon Center never talked to NEADS. They got no help from FAA Headquarters. FAA activated its tactical net (internal) at 8:50; it did not activate its primary net (external) until 9:20. By then it was too late.

UA 93, A Closer Look

John Farmer in The Ground Truth used a decreasing time approach–days, minutes, hours, seconds–to tell the story of 9-11. That approach is useful in telling the story of the counterattack as it concerned UA 93. Recall that earlier we established that the attackers got inside the nation’s decision-making cycle and stayed there throughout the attack. The case of UA 93 illustrates the point.

Newark Airport was ground-stopped soon after 9:00. Following added March 10, 2010. The order to ground stop Newark came at 9:04:40 in the immediate aftermath of UA 175 hitting the WTC. The audio can be heard here. 090440 Newark Stop All Departures UA 93 was still on the ground at 8:42, some 20 23 minutes earlier.

At 9:25, Herndon Center ordered an airborne inventory. UA 93 was hijacked beginning at 9:28, some three minutes later. At 9:26, UA 93 asked for confirmation about the cockpit warning message from United Airlines. A minute later, UA 93 responded to a routine air traffic control communication from Cleveland Center. Within a minute, the attackers began the assault on the crew and then the cockpit.

The Herndon Center counterattack was well executed but never had a chance. The advantage of being inside the nation’s decisionmaking cycle gave the attackers enough of a time cushion to overcome the late departure of UA 93. The counterattack was gaining momentum, but it never caught up. That left the counterattack to NEADS and, ultimately, to the passsengers and crew themselves.

The Air Defense Counterattack

The air defense backup was just four aircraft on the East Coast, two at Otis and two at Langley. No other air base, including Andrews, had the tactics, techniques, and procedures in place to respond on notice. Some argue that Andrews should have responded. The facts show otherwise. It took Andrews well over an hour from time of alert to get a pair of fighters airborne and closer to two hours to get air defense-capable fighters in the air. Even flying a circuitous route the Langley fighters accomplished the same task in 36 minutes.

We discussed the air defense response extensively in the article; “NORAD; should it and could it have done more.” The only time that NEADS successfully tracked one of the hijacked aircraft was just before AA 77 slammed into the Pentagon. NEADS demonstrated that within minutes, given actionable information, it was capable–information and surveillance technicians and weapons directors working as a team–of tracking a primary-only aircraft and vectoring air defense aircraft to the target.

The only other case where NEADS had any amount of time, again just minutes, was AA 11. It is clear from the NEADS tapes that they did find AA 11 moments before impact, but personnel had no time to establish a track.

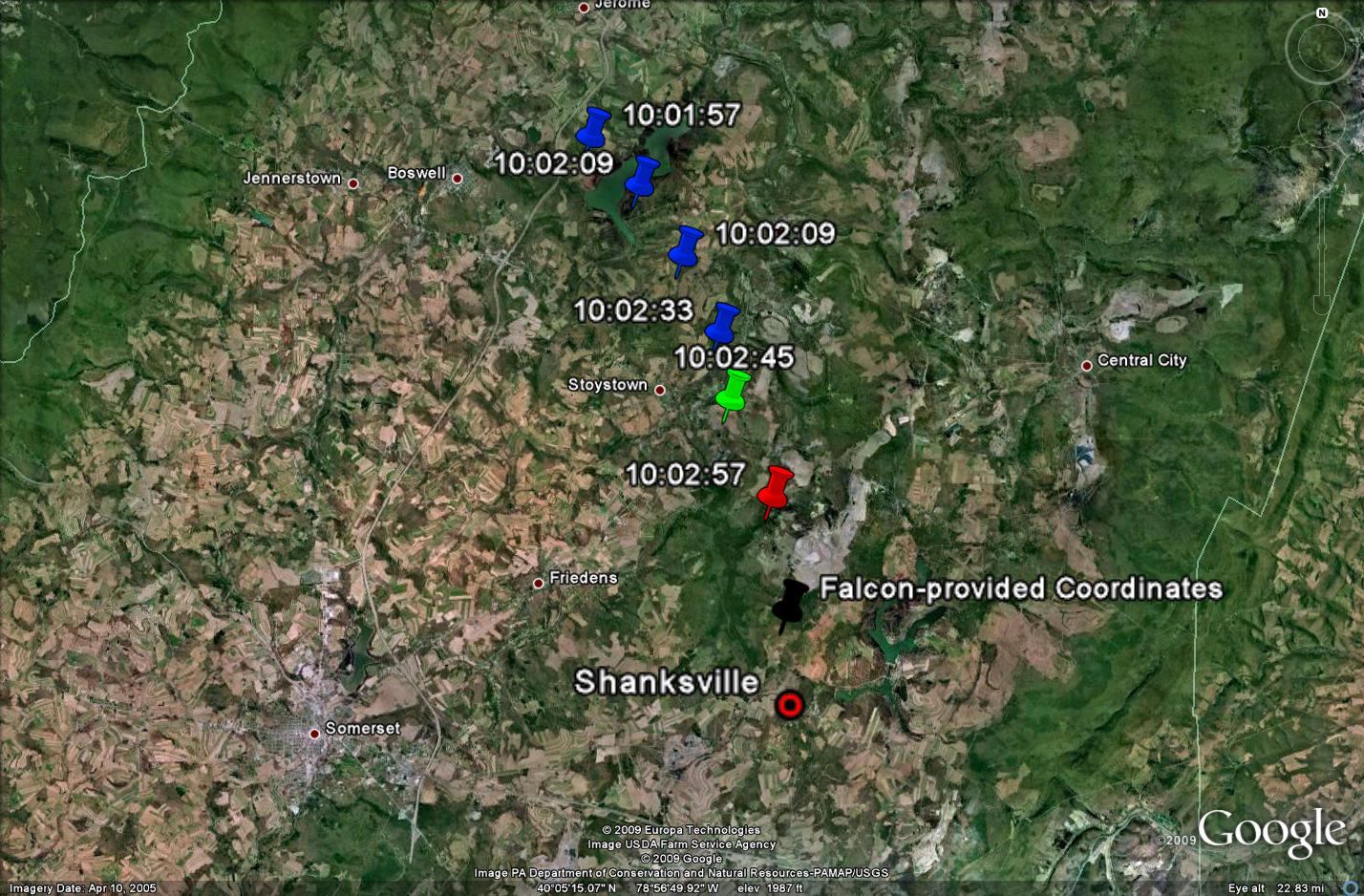

At the end of the battle, the Langley pilots were in place to respond to UA 93. Given that Cleveland Center and Herndon Center knew where the plane was, and given NEADS’ demonstrated performance in tracking AA 11 and AA 77, it is clear that once notified, NEADS would have established an actionable track on UA 93 long before it reached its target area. But NEADS knew nothing about UA 93 until after it plummeted to earth.

Even if the FAA had notified NEADS in sufficient time, being in place and having the authority to do something are two very different things. It is clear that with sufficient notice NORAD could have done something; it is not clear that they should have, as they had no authority to act.

The Aftermath

NORAD segued into Operation Noble Eagle, basically to protect the barn after the horse was stolen. There was no operational imperative for Noble Eagle other than the chilling words, “we have some planes.” That threat led to an extended operation to protect the nation’s skies in the near term, to watch over the rebuilding of the NAS in the mid term, and to continue air defense protection for the long term. Air Force historians will tell the story of Operation Noble Eagle; here we need describe only its genesis.

Operation Noble Eagle, an extension of the existing air defense of the nation, began the moment Colonel Marr began looking for additional assets wherever he could find them. One of the first calls for additional help was to the Langley detachment asking how many planes they could sortie. The answer was that they had two more planes and one more pilot. That pilot, Quit 27, began Operation Noble Eagle when he lifted off, shortly after 9:30 on September 11, 2001.