Transcript of Interview of Lt Col O’Brien

Transcribed by Miles Kara, March 4, 2014

Source is NARA file provided as ANG O’Brien-1.wav

Added, Mar 6, 2014. NARA advises that the interview was conducted on May 5, 2004. NARA will upload the audio file to its 9/11 archives in the next few weeks and it will be publicly available for anyone who wants to listen to the interview

Background.

Commission Staff arranged a telephone interview from an Air Force office where a STU-III (classified phone) was available. That was neither efficient nor effective so I elected to conduct the interview unclassified and recorded it. No MFR was made of the interview.

Following is a final draft transcript of the audio file, subject to additional editing for small segments marked [unclear]. No date was established during the actual recording. I’ve asked NARA to assist in determining the date of the interview. My recall is that the interview took place in 2004.

The Interview

Kara: and how about Colonel Maheney (sp) can you hear me loud and clear?

Maheny: Yes I hear

Kara: OK, we understand the problem and that was part of the ah part of the background I was going into, at least [unclear] looking at events of the day of 9/11, and we are part of a staff of about 80 people sent out through out government. And that really brings us today to talk to you, Colonel O’Brien, and because we are collecting so much information, a wide variety of people we are talking to, our Commissioners have asked that we record our interviews as we move along, and with your permission we would like to record this session today

O’Brien: That’s fine with me

Kara: OK

Maheny: OK

Kara: And for the record, we’ll get everyone’s names. I’m Mr. Miles Kara, 9/11 Commission.

Sullivan: Lisa Sullivan, 9/11 Commission

Air Force Rep: Tom [unclear] [Office of] Air Force General Counsel

Kara: Colonel Maheny go ahead

Maheny: Lt Col Paul Maheny, Staff Judge Advocate, 133d Air Lift Wing

O’Brien: and Lt Col O’Brien, 133d Air Lift Wing is also with you

Kara: Colonel O’Brien let me just start with maybe a couple of sentences on your resume’. How long have you been a member of the Department of Defense and the position you held on 9/11.

O’Brien: I’ve been with the Minnesota Air National Guard since December 1976, and the position I held on 9/11, I was the aircraft commander of Gofer 06. I was also, my full time position here, I am a technician, federal civil service employee, and I was chief of stan/eval [standards and evaluation], in that time as well.

Kara: And for the record, I naively assumed Gofer was spelled G O P H E R, but I find out that may not be so. How is it spelled?

O’Brien: It’s spelled G O F E R.

Kara: Even though it’s from Minnesota, we’re going to do it that way I guess.

O’Brien: Correct, they can only give us five digits in the prefix of our call sign, so we are limited to the F as opposed to the P H.

Kara: And, Colonel O’Brien, as we briefly discussed on the secure line, we are going to conduct this unclassified today, if at any point you feel that we are verging on classified, please let me know. And my reason for, my background for determining that we can talk unclassified is that we hold the air traffic system transcripts of that day, we hold the radar of that day, all of which is unclassified. And we also understand, Colonel O’Brien, and correct me if I’m wrong, you did an unclassified interview with the Department of Defense historian, is that correct?

O’Brien: Actually I did the interview, not with the historian, but I did it with ah, and forgive me for not knowing which one, it was one of the cable channels, The Learning Channel or The Discovery Channel, and that was after I was contacted by public affairs. I believe it was the Department of Air Force public affairs who contacted me, said they had a request to do some research for a [unclear] of the Pentagon, and had cleared it through their staff and they said that as long as I didn’t have a problem with it they were OK with me conducting an interview with them. Since then, I have also done an interview with the Minneapolis Star Tribune, which is a local newspaper here, strictly from a [unclear] on the effect on local people as far as 9/11 was concerned. Just about a week or two ago, I got a request to do an interview with a local public radio station, Minnesota public radio, just to follow up on that. And they just did a real basic interview on the incident that happened that day.

Kara: On that basis then, let’s proceed unclassified and, again, with the caveat that if you understand that we are going to talk about anything classified please let me know and we will adjust accordingly here.

Kara: And according to the mission debrief, Colonel, you were in Washington DC to simply, you were going to ferry some cargo back to Minneapolis, is that correct?

O’Brien: That’s affirmative. We had been on a Guard lift mission down to the Virgin Islands, prior to that. And as an add on to that mission we were supposed to pick up some parts that were supposed to be waiting for us at Andrews Air Force Base, something that only after a few phone calls that morning we found out that the parts had possibly wound up at Dover Air Force Base but they couldn’t verify that for sure. So at that point our Commander at Minneapolis told us just ah to come on home. So, we spent the evening of the 10th September at Andrews Air Force Base, [unclear] remaining overnight, and then we were scheduled to fly home on the eleventh from Andrews to Minneapolis.

Kara: And do you recall what your original flight plan time of departure was when you first decided to come back?

O’Brien: Well, I believe we were scheduled for a 10 o’clock departure, you know the mission was fragged [frag order], this was before we went to Minneapolis on the first day of our trip. And after the determination was made that we weren’t sure where the cargo was, at that point they cleared us to come home whenever we were ready. And so, we really you know didn’t try to make a hard takeoff time, it was just whenever we could get the airplane ready [unclear]. I believe we actually got off at about 9:30 local, Eastern time.

Kara: And what model C130 were you flying?

O’Brien: We fly a C130 H3

Kara: And how is, does, does that model, the H3, carry any armament on it at all?

O’Brien: No, we don’t have any armament on the H3 at all. We do have some defensive systems, we have the capability of chaff and flares, none were loaded on that day.

Kara: And the C130 H3, is, is it, does the H series have an armed model at all?

O’Brien: I’m not aware of any armed H model on the 130’s. I believe all the gunships are previous models to the H.

Kara: And it’s fair to say, then, if you were not carrying any armament that day, there’s no way that Gofer C130 that you were flying, C130H3 model, engaged either American 77 or United 93 that day.

O’Brien: Ah no, there was no way we would have had any way of engaging those aircraft.

Kara: Nor, as one of the popular myths out there on the fringes has you firing a missile into the Pentagon, you had no capability to do that either, is that correct?

O’Brien: That is correct

Kara: OK, I just, and the reason I ask those questions simply is to get that on the record up front so that we can uh, we are working, Colonel O’Brien, to tell the story of 9/11 as accurately as we possibly can. And that involves us talking to controllers, to pilots, to anybody else who was involved that day, and we are trying to understand the events of the day almost as if we had been in their seat, that day. So that will explain some the questions I am going to ask you.

O’Brien: Understand.

Kara: What was your situational awareness of the events in New York before you took off?

O’Brien: We had no knowledge of anything that had taken place in New York. The first time we knew anything about the events that took place in New York were as we were departing the Washington DC area. It was a frustrating feeling because knowing we would have been in a better position to orbit over the Pentagon and possibly help out with any kind of rescue efforts, a birds eye view of maybe telling them of what was happening traffic wise or where they possibly effect the best rescue effort. And, when they asked us to depart the area one of the first things I did was direct one of our crew members to get on one of our navigational radios and call the [unclear] that shared the same frequency spectrum as the radio stations and so we attempted to get a Washington DC radio station on that radio to learn more about what was going on behind us. And the first thing we heard when we got the, to my recollection, first thing we heard when we got that [unclear] radio tuned up, was that the second aircraft had impacted the world trade center, or at least a aircraft had impacted, I’m not sure about the second one. As soon as we heard that we knew that, our suspicions were that this was bigger than just an attack on the Pentagon.

Kara: And that was when you were in the air that you heard that?

O’Brien: That’s affirmative

Kara: OK, And on the ground, and Colonel, we pulled your flight strips from Andrews Tower, and we’ve got two flight strips on you. And the first one is at 1330, 9:30 Eastern Daylight Time, and we believe that was your original takeoff scheduled that was entered into the flight data system. And, then later, we have a second flight strip which is 1333, and we believe that is the flight strip that was executed when you actually got wheels up. And that seems to correspond with your recollection that you were up at about 9:31?

O’Brien: Correct

Kara: And what I’d like to do now for you, Colonel, is start playing for you some of the tapes we have from the air traffic control system. And the purpose of the first segment is to show that while you were on the ground at Andrews you were actually delayed for a couple of reasons as you took off and you actually got off a little bit later then you might have otherwise. So let me play that first segment, and I’ve got the recorder with the segment on it close to the telephone and hopefully you can pick it up at your end. So let’s try it. I’ll play it through until you are off the ground at Andrews and then we’ll stop and chat about that briefly. So here we go.

[played tape from Andrews Tower]

Kara: Could you hear that all right Colonel O’Brien?

O’Brien: Yes I did, some of it was a little garbled, but I got the gist of it.

Kara: Right, do you recall those conversations?

O’Brien: Yes, I do. First time I’ve heard them, and it’s a somewhat eerie to hear them again after all this time.

Kara: And it’s a little bit eerie in that the time frame we are talking about Colonel, and my apologies if it causes you to think in an emotional area, But had you not been delayed for three minutes you would have been out there in the flight path of American 77, as it turns out. And we know at that time you had no situational awareness that you knew that 77 was out there when you took off, is that correct?

O’Brien: That’s correct

Kara: And the reason that you were delayed, there are at least two, perhaps three reasons, and there, and, let me recount them as I understand them, and if that’s not correct let me know. You were first held because of the wake turbulence for a seven four heavy [Word 31] that was going off. That was one of the “kneecap” [NEACAP]. I think you were held briefly a second time because of a grass cutter. Not sure on that. And then third, there was a helicopter that was coming across and you were held up for that. Does that square with what you remember?

O’Brien: That’s affirm. If you like I can elaborate a little bit on the seven four seven, but ah…

Kara: Yes, yeah, would you please?

O’Brien: Well, my recollections on the seven forty seven, and I remarked to the crew while we were starting our engines, as I remember the seven forty seven cranking up, we were facing them. We were headed, our aircraft was pointed southbound towards where they keep the seven forty seven, Air Force One, and the other aircraft. And uh I remarked to the crew that I thought it was unusual that that seven forty seven had gotten started up and had departed in a fairly short time span. I don’t remember the exact time, but I know that, for example, for our aircraft with a four-engine start, typically under normal circumstances, it might take us fifteen minutes or so to get all the engines started, all the check lists accomplished and [unclear]ready to taxi. Seemingly, this aircraft had departed a lot quicker than that, but not knowing anything else that was going on, you know, [unclear] that airplane got off fairly quickly.

Kara: Do you recall if he got priority over you, were you held up so that he could go first, or not?

O’Brien: No, I don’t recall any priority like, you know, when we call for a taxi, I don’t recall any delays, you know, you have to stand by and wait for the seven forty seven. It may have happened, but I don’t recall that being any kind of conflict at all. It was just a matter of, you know, I think we maybe both started the starting engine sequence at about the same time. It’s just a guess because they don’t have propellers like we have, but ah, it seemed like they had gotten off much sooner than normal [unclear] departure would be.

Kara: And that’s normal to hold up for turbulence they cause when they take off?

O’Brien: That’s correct. There is a wake turbulence separation criteria that are in effect and they just hold us until they feel the wake turbulence from a departing heavy aircraft has dissipated enough to make it safe for departure.

Kara: OK, the next segment I’m going to play for you, Colonel, is ah, I’m simply going to play it and see if you remember hearing it. It is not directed at you, but it is a conversation that occurs in the air between one of the two towers and another plane that is in the sky.

[side direction to Sullivan]

[Misplay of previous clip]

[side direction to Sullivan]

[A National Tower clip, a discussion of the situation in New York, but not clear, second plane into second tower]

Kara: Do you recall hearing anything like that while you were on the ground Colonel O’Brien?

O’Brien: No I don’t.

Kara: And you might have heard in the background Andrews calling for another release; that was the release on you. So this conversation was going on in the air. I think that’s Andrews, excuse me I think that’s National Tower and there was no reason for you to be on their frequency at that time. I just play that for you so that you have situational awareness as we now get you up in the air here.

Kara: Let me continue playing

[Played conversation between National Tower and Gofer 06 immediately after takeoff. Gofer 06 has the unknown in site and identifies it as a seven five seven. Gofer 06 is directed to follow the aircraft]

Kara: Colonel, let me just interject and I forgot to tell you that at the beginning, I have voice activated taped this so there are, the gaps that were there have been taken out and this is not in real time. [dead space and unrelated transmissions were removed to condense the information for the interview]

O’Brien: OK, I understand.

Kara: And, it uh, took you a while to get the tower to understand that you weren’t Gofer 86, you were Gofer 06.

O’Brien: Ah Yeah, that happens once in a while, it’s you know, not common, but it happens. So you just try and make sure that you correct them. It’s standard procedure to make sure there aren’t any confusions. Because sometimes there are similar call signs, either the suffixes are very close or the prefixes are close. And so, in case there was another 86 aircraft out there I didn’t want them to confuse us with them. So, consequently I am a little bit stubborn and try and make sure they have the right call sign.

Kara: And we appreciate that. And just for your situational awareness, you might have heard in the background, you’re on the Tyson at ah National Tower, and in the background you might have heard Krant position as they just became aware that they have a fast moving aircraft, so that’s going on in the background. And they’ve become aware, in real time, that they actually have a military aircraft up there that they can, that they can divert and that’s in fact what they did. So let me just continue this segment and then we can talk about it.

O’Brien: OK

[Continues playing tape from National Tower]

Kara: You recall that, Colonel?

O’Brien: Yeah I do, yes sir I do!

Kara: And, I have one clarification that I would ask. You make a report that the aircraft is down. And then later you say it’s into the Pentagon. When you use the phrase down, there, you mean down on the ground, is that correct?

O’Brien: That’s affirmative. I probably should have used some other terminology other than down, but that’s the first thing that came to mind. I witnessed an aircraft crash when I was back when I was in pilot training one of my class mates crashed in front of me on final and, so I’d seen that signature fireball and smoke [unclear] come up once before from a jet fuel explosion like that and I don’t think it happened quite that quickly. I don’t think it happened that quickly. You mentioned something about how you have the tape [unclear] off just a little bit. I recall it being a little bit of a delay from the first time I reported the aircraft until I reported the aircraft had went down.

Kara: And what I did Colonel was I compressed about three minutes of audio down into the segment that you heard hear. And I wanted to make you aware you are not hearing it in real time; I just simply did that in the interest of time.

Kara: When you identified the plane as a seven five seven did you have any indication at all of the company?

O’Brien: No, I didn’t at the time. And I remember when I debriefed with the folks in Youngstown, Ohio, that I was not able to really give them a commercial carrier. I think the aircraft was banked up, I recall, quite a bit steeper then what your typical aircraft, commercial airliner banks for a turn. I want to say it was between 30 and 45 degrees of bank constantly when he went by us at our 12 o’clock and passing through our one to two o’clock position. We were pretty much looking at the top of the airplane. So, I remember seeing what appeared to be almost like a red stripe at the root, the wing root of the, ah, it would be the right wing, I guess, as they were passing by us. And in hindsight I realize now that it was probably the American Airlines, you know, their signature paint job that they have along the wing probably reflecting off the wing. But, all I remember is a silver 757 at that point and I believe that is what I debriefed to the Intel folks at Youngstown [unclear].

Kara: And it was clear to you that that was a seven five as opposed to either a seven six or a seven three?

O’Brien: It was definitely a 757 [unclear]. Where ah, where ah close enough, I guess the models are close enough. Seven six is obviously, you know, a little bit bigger than the seven fifty seven, but they’re fairly close in size and I guess I was correct in my initial assumption when ATC [air traffic control] asked me what type of aircraft that was. Subsequently, when I debriefed with the folks at Youngstown I, you know, said well I’m not quite sure, it was a seven fifty seven, possibly a seven fifty seven, but I guess my initial recognition of the aircraft in conversing with ATC was correct, that is was a seven fifty seven.

Kara: And it’s quite clear to us as we listen to these tapes that you gave a clear identification of the type aircraft to air traffic control in near real time. And as you are probably aware in the news it doesn’t get sorted out nearly as fast as you had it sorted out to air traffic control. And the question we have is, were you on the air with anybody else at that time? Were you with a military controller of any sort or talking to the military?

O’Brien: No we weren’t. Sometimes we are, we have our radios tuned up to the command post that we just departed, in order to give them a departure call so that they can plug it to the command and control system for the military. And that just updates our time so that the folks at our home station will have a better idea, you know, when to expect us for arrival. But we were not conversing with Andrews command post at that time.

Kara: And, the, so, the only military entity you would have been in contact with normally would have been a command post, in this case Andrews. And it was the case on that morning that you were not on freq with the Andrews command post?

O’Brien: Not at that time, no. No, we weren’t, we weren’t conversing with them at the time. And I can’t really recall whether or not we had made an off call to Andrews command post. Things were happening fairly quickly and any time you are operating an aircraft in the, in the Andrews area, you got a number of airports there, things are real, real busy. And my assumption is that we probably hadn’t even initiated our off call to command post just because things are a little bit more saturated as far as ATC calls and directions, it being a fairly busy environment there around Washington DC. You really have to listen up on the radios and not miss any calls to yourself because they are typically stepping you up in altitude only a thousand, two thousand feet at a time and giving you fairly precise vectors to keep all the traffic separated.

Kara: And when you say off call, what does that mean?

O’Brien: Departure call.

Kara: Departure. Oh, OK, I got it. And, a departure call, a courtesy back to the base command post, could have been done, but was not.

O’Brien: That’s, that’s to the best of my recollection. I don’t recall. A lot of times when we have a navigator on board we will delegate that to the navigator and let him make our departure call back to the command post so they can update the system. And I, I’m sorry I really don’t recall whether or not Colonel DeVito had made that call or not. I would have, I know the way I run things on an airplane, I would have delegated that to the navigator just because it is a busy area and it was the co-pilots [unclear] that day. Even though I was in the left hand seat as the aircraft commander I was working the ATC radios that day and I’m sure I would have delegated the UHF radio which we use to stay in contact with military command posts and the navigators, ah..

Kara: And that was Colonel Devito?

O’Brien: That’s correct

Kara: What’s his first name?

O’Brien: Joseph

Kara: Joseph. And is that Lieutenant Colonel or Colonel?

O’Brien: He’s a Lieutenant Colonel

Kara: Lieutenant Colonel. And what ah, as you think back on that, what other traffic was there in the area that you can recall?

O’Brien: You know, I don’t recall, I’m sure there was other traffic. But, I don’t recall any other traffic, I mean it is just a very busy environment and to see, you know, traffic out there and to notice everything that’s in the area, you’re busier than you would want to be, especially when you are trying to listen up on the radio freq, ATC calls and all that, of course we are looking at things but we are not commenting and I’m not, you know registering and recording those things in my mind as far as, it would be unusual to see four or five different airplanes in that environment there, so you’re, for the most part, just clearing the area in front of you. And, of course, we’ve got a what we call a TCAS, it’s a, oh what should I say, it’s a piece of equipment that allows us to identify other aircraft out there that have transponder codes. And, between clearing out visually and using the TCAS equipment that we’ve got in the aircraft, and then [unclear] on ATC, that’s how we basically clear [unclear] other aircraft that might be in the area.

Kara: And the only traffic that was of concern to you for safety or safety reason was the traffic that was pointed out to you?

O’Brien: That’s correct. And I had ah, to the best of my recollection I had noticed him before the ATC call. I believe I first saw him about my ten o’clock position and then when the controller pointed the traffic out to us on the radios it was a, fairly obvious you know what airplane they were talking about, [unclear] sounded what should I say, kind of incredulous that we wouldn’t have seen that airplane because he was as close as he was to us. And that surprised us when he asked us to identify the airplane. Because, typically, ATC knows more about the aircraft than you do as far as the identity, they have an individual strip on each aircraft that identifies their call sign, type aircraft, the type carrier, the carrier that was operating that airplane, and so on and so forth, so when he asked us what kind of airplane, it was it was a very unusual request.

Kara: And, based on our review of the radar and the air traffic control tapes and any other information we can get our hands on, the only other aircraft that we’re aware of that day that you may have been aware of either visually or on radar, first of all, did you see Word 31, the seven four, out in front of you?

O’Brien: I don’t recall that aircraft, I’m sorry.

Kara: And there was a helicopter that took off from the Pentagon oh a few minutes before you came across the Potomac, and he was headed northbound. You recall seeing a helicopter in the area?

O’Brien: No I don’t.

Kara: And the only other two airplanes that I’m aware of that are of interest, there were two Bobcats, and I think those were Air Force [unclear] out of Dover, but they were well at altitude, the were at 17 and 21 thousand on top of you, you recall either talking to them or being aware of them at all?

O’Brien: No we were not, we were certainly not communicating with them and we didn’t recognize, or I shouldn’t say didn’t recognize, but we didn’t see them as a crew, being down at 3 thousand feet or so we were our scan wouldn’t have gone up that high.

Kara: And then as ah you were, how many minutes or miles were you behind the plane you followed? Behind seventy seven?

O’Brien: Oh, behind flight 77?

Kara: Yeah

O’Brien: There was a delay from the time that they asked or that I offered to them, you know the aircraft rolling out on a northeasterly heading and still in a descent, I’m not sure how long of a time frame that was, but as fast as that airplane was going, I’m sure there was quite a bit of separation that took place between us and that aircraft before they then asked us to turn and follow that aircraft. And I remember, vaguely remember, trying to keep the aircraft in sight. And every once in a while we would get a glimpse off of the wing tip or whatever, but it was early in the morning, [unclear] practically 9:30 or 9:40 or so, and the sun was still somewhat low on the horizon. And with the east coast typically being hazy with just moisture and pollutants and things like that, it becomes a little bit more difficult when you are looking for the traffic eastbound, you know looking toward the east looking for traffic through the sun haze it becomes difficult and so we were really straining to keep that airplane in sight until the impact on the ground there and it became obvious where the aircraft was down.

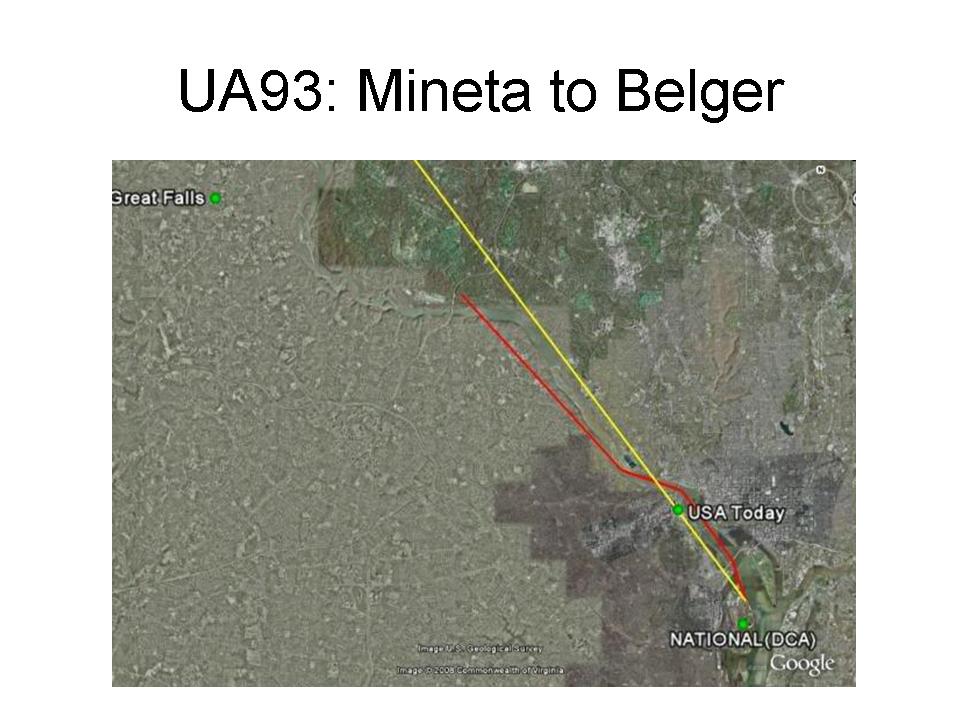

Kara: And we have the radar reduction files from the 84th Radar Evaluation Squadron at Hill Air Force Base and it looks to us as, as though, we analyzed that data, that it looks like you were about two minutes behind the aircraft. When you were able to make your turn and come and vector behind him it looks like you were about two minutes behind. I just point that out to you so that you are aware of it.

O’Brien: OK

Kara: And then you were asked to orbit the Pentagon as I recall, but you were called off of that. Could you walk us through that for a minute or so?

O’Brien: Well, initially, they gave us that heading of two seven zero, and, I can’t remember exactly when I took the aircraft from my co-pilot but I believe it was after that instruction. We were getting closer and closer to the Pentagon and I could see that the vector they were giving us could possibly take us through the plume of smoke that was coming up from the Pentagon. And, for what ever reason, I still didn’t know anything about the aircraft menacing the World Trade Center, but it was somewhat obvious to me that a pilot worth his salt would not have taken a disabled airplane into the Pentagon. And so, right away my suspicions began to, you know, rise that this was possibly a deliberate act and not knowing, you know, what might be coming up in that smoke, whether or not they had any kind of nuclear, biological, or anything like that on board the airplane, for a terrorism situation like that, I thought it was not a good idea to fly through that plume of smoke coming up from the Pentagon. And so I believe that’s when the notion came to me that I should not take the airplane, I had taken the airplane and I realized that at that point I would have to turn back to the right a little bit. We were heading approximately zero nine zero, you know heading still heading toward the Pentagon when we got that request from or direction from ATC to turn to a two seven zero heading. At that point I made the decision that we were going to turn a little bit to the South and basically enter a left hand orbit around the Pentagon, around the side of the Pentagon, which would keep it on my side of the airplane. I thought that was best since I was flying the airplane now. Then I thought, you know, about possibly trying to set up an orbit around the Pentagon to effect some kind of rescue attempt or whatever, and, or help out with any other information. I could possibly give them a birds eye view there and they were fairly emphatic about asking us to depart the area there at two seven zero at my [unclear] altitude. So, at that point I thought I’m not going to argue with ATC, we’ll just follow their direction and go ahead with whatever they wanted us to do.

Kara: Yeah. And for those of us who are not pilots, or rated, when you say your side is that the right side or the left side of the aircraft.

O’Brien: It’s the left side

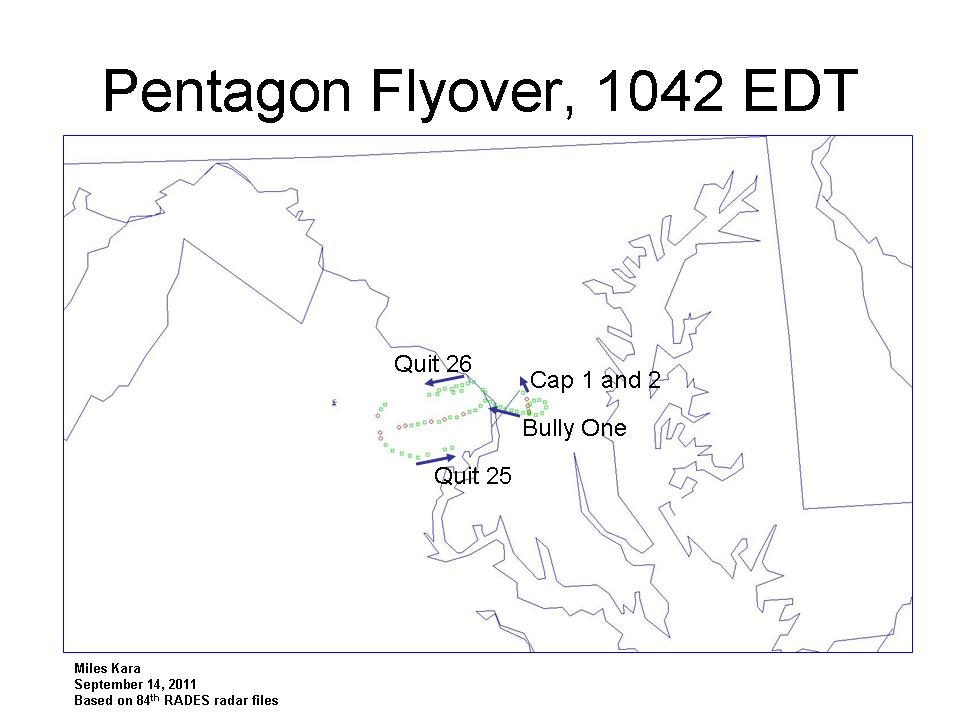

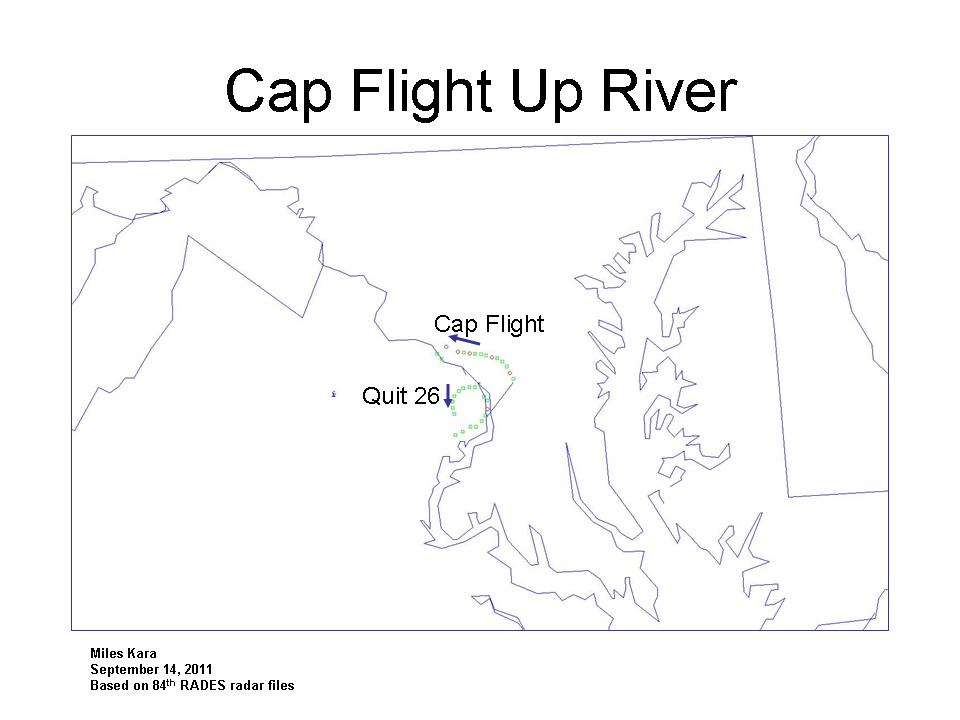

Kara: Left side. And the time you’re in the vicinity of the Pentagon, and that’s just around 9:40 Eastern Daylight time. We you aware of or did you see any fighter aircraft or other military aircraft?

O’Brien: No, no we weren’t aware of any fighter aircraft?

Kara Ok. And then you proceed on your way, a heading of three ten, eventually, and you’re headed up towards Pennsylvania and I’d just like to play a little more audio for you. And what we have is, well the Tyson position is vectoring you as we just learned. The Krant position, on the other hand, is picking up situational awareness and a little bit of that was in the background. But I’d just like to play for you the other side of the conversations that were going on in the Tower that day. So, if you’ll just bear with me a minute.

Kara: Should be able to start it up.

[An audio compilation. The Dulles TRACON clip sounding the alert, conversation at National and Andrews ATC facilities, to include Venus 77]

Kara: OK let me stop it there. Colonel, that was the other side. What you heard in the background is a, a voice, a female voice said, National, anybody. That was the first identification of a fast moving aircraft approaching the DC area, and that was at about 9:33. And that’s just about the time you took off, so we have Dulles reporting that to National Tower and at the same time they are lifting you up. And we got both planes, if you will, coming toward the DC area, or toward the Pentagon area from different directions. At one point, and I don’t think you heard it, but the original point out on the 757, a voice in the background said, oh, you mean that Gofer guy. And he says, no, no, it’s ah it’s the “look” point out that I gave you.

[Comment. Researchers familiar with the National TRACON radar can correlate the “look” point out to the “S” tag which shows up on the primary only track of AA 77 in this time frame]

Kara: Either that day or afterwards were you aware of any of that juxtaposition of your flight with the fast moving aircraft coming in bound?

O’Brien: When you refer to the fast moving aircraft are you referring to flight seven seven?

Kara: That’s correct. It’s not, no one knows it’s that it’s seventy seven, so when Dulles first gives that point out there, they pick up a primary only coming in, and that’s how it’s announced over the air traffic network.

O’Brien: OK, no, I was not aware of that fast moving aircraft. And like I said earlier, I believe I had first picked the airplane up, and I’m guessing we were ah at 3,000 feet, maybe had just been cleared up to 4000 feet, when I noticed the airplane. He was up a little bit higher than us at that point and then when ATC asked us again if we had the airplane in sight he had continued his descent down, was in a fairly, like I said, steep bank turn to the right at about our 12 o’clock position and at about the same altitude, I would say was about 3500 feet or so.

Kara: And as you may have heard, shortly after you reported the Pentagon crash and it became aware there was a ground stop in the DC area. And had you been further delayed until after that you wouldn’t have gotten off the ground.

O’Brien: I understand that.

Kara: Did you hear that ground stop come out over the frequency?

O’Brien: You know, I don’t recall hearing a ground stop, per se, over the frequency. If I did, it’s been so long that, you know, that memory has faded. There’s only certain things that really that stick out vividly in my mind.

Kara: Let’s take you up now on the three ten leg, and at some point in time you’re made aware of another situation that’s developed. And I don’t have the page with me from Cleveland Center who I believe was talking to you but what you recall [side comment to Sullivan], what you recall about the second event that day?

O’Brien: Well the second event, I had asked the crew if everyone was OK to continue on. This was after the witnessing the crash at the Pentagon. All the crew members came back and reported that they were OK to press on. That was my biggest concern at that point was how was everyone was doing. So we decided to continue on back to Minneapolis. We had been handed off from departure control to center [Cleveland]. And I believe it was the first center controller, Cleveland Center, who had pointed out traffic to us at our 12 o’clock. Couldn’t give us an altitude. And so we did our normal scan looking for traffic, go out [unclear], you know, increasing above and below. We really couldn’t pick any thing out as far as, you know, the traffic was concerned. And at that point we reported back to him that we didn’t have any traffic in sight. So he gave us a vector, about three six zero, basically a right 90 degree turn to head us to the north to deconflict with, should that traffic, you know, happen to be at our altitude. Shortly after we rolled out of the turn that another crew member [unclear] in the back of the aircraft reported to me smoke off the left side of the aircraft. And I turned I looked right away and saw, you know, the black smoke coming up from the ground. This one wasn’t right after the impact, so I personally I didn’t see [unclear] you know, that yellow plume of flame or anything like that, all I saw was the smoke coming up from the ground. And at that point I reported that smoke to Center and gave them an approximate position, you know Paul and I [unclear] just about 20 miles away. And I think he came back and replied that he had lost the traffic that he was pointing out to us, about seventeen or eighteen miles, the two were close enough that I was sure that you know what he was pointing out to us possibly could [unclear relate] to the smoke coming off the ground.

Kara: We have you from the 84th Radar Evaluation Squadron, uh air traffic was accurate. The inbound path of a primary only, which we now know to be United 93, was at your twelve o’clock. It crashes near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, at 10:03 and at about that time I have you on radar evaluation reduction as just crossing from Maryland into that narrow projection of West Virginia and you are not quite in Pennsylvania, yet. And, at that point that you were vectored 90 degrees to the right, was that when you were 40 miles away, or was it further up?

O’Brien: Ah no, it was about 20 miles away, was my estimate that we saw this smoke, and that was just a rough guess on my part when I reported back to Cleveland Center, told them that we had smoke coming off of the ground. I estimated it to be about 20 miles.

Kara: Off the port side, right?

O’Brien: That’s correct, off the left wing tip, our nine o’clock position.

Kara: We have, he vectored you, at about 10:04 he vectored you 90 to the right and at 10:07 the controller brought you back again on course, at about 10:07, that’s about four minutes after the impact of United 93 into the ground. What was your awareness of other aircraft in the sky?

O’Brien: Well, ah the only thing I saw that I, you know, vaguely remember and I didn’t think it was significant at all, I saw a smaller white aircraft at a lower altitude and we were up high enough that it would have be difficult for me to, you know, give an exact altitude. But, if I had to guess right now, trying to remember what it looked like, I’d say it was, you know, below ten thousand feet, possibly down around five or six thousand feet, and if I remember correctly it looked like a white business jet and I believe it was north bound when I saw it. That’s the only other traffic that I recall seeing in the area beside the, you know, the smoke plume coming off of the field.

Kara: Let me come back to that business jet in a moment. But let me just simply ask you, do you recall seeing any fighter aircraft or any other military aircraft in the vicinity or on your flight path that day?

O’Brien: No I don’t.

Kara: OK, and I appreciate that. That’s helpful to us that you have that good recall.

Kara: The business jet, again, thanks to the 84th Radar Evaluation Squadron, we believe that to be a Falcon jet, November 20VF that was, it was at altitude coming up oh it was at about zero three zero [azimuth] coming across the Pennsylvania border from Ohio, and was vectored by air traffic control from altitude down to, and I’m going on memory here, but it seemed to me eight thousand feet, which would square with your recall. That airplane actually did one three sixty loop just, just above the crash site and at uh at10:14 EDT, this would be ten, eleven minutes after the impact. It was immediately at nine o’clock from your left hand seat, which, you said you were on the left side, right?

O’Brien: That’s affirmative

Kara: That aircraft would have been at, uh, let me get my clock right, would have been at nine o’clock if you had looked out the window. And you think you saw him at about that time, perhaps?

O’Brien: That’s affirmative

Kara: And you were not then vectored to do anything else concerning that crash, and you continued on and landed uneventfully at Youngstown, Ohio.

O’Brien: That’s affirm. We get handed off, I believe, to another Cleveland center controller shortly after that. And it was then that he was somewhat hesitant in asking us, you know, what we should be doing at that point. I can’t remember his exact terminology, but it was something to the effect, I’m not sure if I can ask you this but can you tell me what you guys are doing? And I just, you know, basically relayed to him that we were an air national guard aircraft heading back to Minneapolis. And he came back with something to the effect that well I’ve been told to get all commercial aircraft on the ground. And you’re a military aircraft so, you know, might want to check with your folks and see, you know, what they want you to do. And so I checked, I looked at one of our navigational charts and saw that Youngstown Ohio was the closest, or to me it appeared like it would be the best divert base if in fact if we had to divert someplace because [unclear] was going on. So I initiated contact there with command post there at Youngstown and they gave us instructions to the effect that we should land at their location, there.

Kara: As I listen to the tape from the Cleveland controller, it seemed like he was a bit challenging of you. He knew that all our planes were supposed to be on the ground and he was a bit challenging of you of why you were even in the air. Do you recall that?

O’Brien: Yeah, I don’t know if he was challenging us or if he was just uncomfortable with asking us, you know, and I thought back in hindsight that if he was, you know obviously he had must have had a strip on us, just like every other controller has, you know, with basic information of departure point and destination. And, you know, my initial reaction was well if he saw us departing out, out of Washington DC, out of Andrews Air Force Base, at approximately the same time that the terrorist incidents were taking place at New York and the Pentagon that we might be some kind of an evacuation airplane. And so, that’s the, I guess, the hesitancy I heard in his voice, not so much a challenge as he was somewhat uncomfortable even in asking us what we were, you know, doing. And, when I relayed to him that we were just an air national guard C130 heading back to Minneapolis that is when he made the recommendation that we probably contact someone in our command and control to, you know, see if they had further instructions for us.

Kara: By this time in the Washington area, and perhaps elsewhere, Andrews Tower, specifically, and later Dulles Tower, were making the following kinds of announcements. At 10:05 EDT, and at that point you would have been just crossing, you would have just turned right vectored to 90, 90 right and crossing into Pennsylvania, Andrews Tower broadcast on guard that any airplanes violating Class B airspace would be shot down. And then, about ten minutes later, at 10:15, there’s a similar call for Washington, excuse me Dulles Tower making the exact same pronouncement to all airplanes in the sky, any airplanes approaching Washington DC. Do you recall hearing any of those announcements on guard or any other frequency?

O’Brien: No I don’t. And, I hate to, because it’s been two and one half years and I know you are playing back all the tapes, but, and I could have, you know I hate to say this, I could have imagined this after the fact. But when we were initially pulled to turn to the 270 heading, and I can’t remember how many radio transmissions it was after this, I vaguely remember one of the [unclear] guys saying that, you know, we have fast movers coming into the area and that is why they needed us to get out and the assumption that I made was, if in fact this is a terrorist incident, they just want us, you know, have the proper sorting out, good guys from bad guys, they just wanted all the airplanes they were talking to, to vacate the area. And I don’t know for sure if that was on the tapes or if they gave that to us, but I vaguely remember, you know, remember something to that effect.

Kara: And the announcements that are referred to, we pick up on Washington area air traffic control towers. And I don’t remember whether center, Washington Center put that out or not, they might have. But at that time you were well within Cleveland Center’s airspace, and I don’t recall Cleveland doing that and that’s why I simply asked you if you, you had heard a very precise announcement from any center or any tower that you might be shot down if you went back to Washington.

O’Brien: No, I don’t recall hearing anything like that at all.

Kara: OK and ah, let me just ask you squarely again Colonel, in reference to your proximity to the crash site of United 93 near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, it’s a fact that you in no way, shape, or form, were armed that day, and you did not see any armed military aircraft, air defense fighters, or other aircraft that could have been involved in the downing of that aircraft.

O’Brien: No I didn’t

Kara: And, again, I thank you for that kind of precise statement because that will be very helpful to us.

Kara: As I go back over your mission debriefing there’s just a couple of points I’d like to ask you about. In one there was an inference that you were going to be or might have been interviewed by the FBI, were you so interviewed?

O’Brien: Yes we were. When we arrived at Youngstown, Ohio, I immediately asked to talk to the senior ranking person at the base operations building there, and I believe it was the Ops Group Commander that I talked to, but I couldn’t be for certain who that was right now, and basically told him that I think we should go to some place and discuss what we had seen. And, at that point I think we got a real basic debrief with the intel folks at Youngstown, Ohio, the military intelligence section at Youngstown. And then it was shortly after that that they said that the Cleveland, I don’t know if it was Cleveland, but they said the FBI wanted to come down and do an interview with some of the crew members, I thought they said they were coming from Cleveland.

Kara: And do you recall when and where that interview was conducted?

O’Brien: The interview was conducted back in the base operations building, actually, back in, but I believe it was right in the same intel, the secure area inside the intelligence section at Youngstown, the FBI [unclear]

Kara: That was on 9/11 and that [unclear]. Do you recall how long that interview lasted?

O’Brien: No I don’t, I would just guess that it was about15 to 20 minutes.

Kara: And then you used nomenclature that is interesting to me and that I am not familiar with. And I’ll just give you the nomenclature that you used and maybe you can tell me a little bit about it. I think you are talking about the modes on the airplane and you talk about “stick paint.”

O’Brien: That was a typo. And I commented, it was interesting to read the transcribed transcript of the taped interview that was done by our folks here at the Intelligence Section here at the 133d, because that was meant to say skin paint, S K I N.

Kara: That makes, in other words primary radar.

O’Brien: That’s affirm. We have a fairly sophisticated radar in the H3 model that we hadn’t had prior to this, and its got various modes in it, its got a weather mode, and its got a [unclear] mode, and its, one of the modes happens to be skin paint that we can range out to approximately 20 miles for primary targets. In other words if the aircraft is made of metal we’re going to pick it up on our radar. And we have various gates, air speed gates that we can set up to illuminate slow moving traffic or fast moving traffic, whichever. And so, typically we operate we call a skin paint medium mode. Where, what it basically does is eliminate all the ground clutter because it will actually pick up if you leave it at low mode, it will actually pick up traffic on highways, things like that. So the skin paint was a reference to the low mode radar.

Kara: And you can only go out 20 miles with that?

O’Brien. That’s affirm, that’s the maximum, if we’re really tight to you know, be very precise it’s got lower settings, we can get it all the way down to a mile and a half, where the bottom of the scope, top of the scope is a mile and a half out.

Kara: And in its, in its final minutes United 93 was at 8000 feet, and its altitude, or altitude above ground was probably [unclear] beyond your skin paint capability?

O’Brien: Well, you see, there’s a beam of radar, so it’s not, you know it can’t paint from the ground up to infinity, anything like that. I’d have to get my tech order manual out to give you an exact, you know how big the slice of airspace it was looking at based on a certain distance as far as the maximum range of the radar is concerned. It’s not looking at a very wide slice of airspace, to my understanding.

Kara: Do you recall then, you never had United 93 on your TCAS or any kind of radar display?

O’Brien: Now, refresh my memory, 93 was

Kara: That’s the plane that crashed that you observed the smoke.

O’Brien: OK, no, that one we were not painting on skin paint nor were we painting it on TCAS.

Kara: OK

Kara: Colonel, we’ve covered quite a few items today, and based on my, ah [unclear] that I’ve given you in terms of some of the radar reductions I have and the tapes that you’ve listened to, is there anything I haven’t asked you about that I should know about in your observations that day?

O’Brien: No I can’t say that there’s anything at all, it’s interesting to listen to it again and kind of relive it.

Kara: It was my pleasure, Colonel, to play back for you your own voice that day. Have you been interested at some point in time that we were going to call you?

O’Brien: Had I been interested?

Kara: Had you been interested or not in whether or not the 9/11 Commission was going to reach out and talk to you?

O’Brien: You know, it hadn’t really crossed my mind, although you know ever once in a while when I think it has died down, I’ll get a request to you know do another interview or whatever, so nothing ever surprises me anymore. It was interesting to hear from the 9/11 Commission, because I didn’t know how you know thorough they were going to be. And, so, anyway.

Kara: And your specific assistance to us today, as you’re well aware, Colonel, the public stories that are out about the day of 9/11 are loaded with myths, and mythologies, and incorrect interpretations, and just plain wrong stories out there. And part of it has to do with the ultimate fate of 77 and 93. And you’re an eye witness that day in both instances and your clear recollection has been extremely helpful to us and we thank you for that.

O’Brien: OK, I’m glad I was able to help the Commission out.

That concluded the interview. Kara, Sullivan and O’Brien talked briefly at the end, nothing substantive.